Issue #59 // Castles on Quicksand

A Consumer Health Tracking Story

Enjoy this issue? If so, you can show your support by tapping the 🖤 in the header above. It’s a small gesture that goes a long way in helping me understand what you value and in growing this newsletter. Thanks!

Issue № 59 // Castles on Quicksand: A Consumer Health Tracking Story

Last month, a friend showed me the Whoop app’s latest feature with a level of enthusiasm typically reserved for winning the lottery. "Look!," he said, pointing to a number on his iphone screen, "My biological age is three years younger than my chronological age!"

Hearing my friend wax poetic about his Whoop Age left me in an uncomfortable position. As someone who founded a wearable biosensor company and understands the limits of current sensing modalities—and actively works on developing new protein biomarkers—I had a strong inkling that this measurement was less than accurate, to put it kindly. After all, his Whoop wasn’t measuring his telomere length, DNA methylation patterns, or protein aggregation markers. It was measuring his heart rate, HRV, blood oxygenation, skin temperature, and movement, then applying algorithms trained on population-level data to generate what appeared to be a legitimate biological assessment. This disconnect between the information Whoop claimed to provide and what their devices actually measures was surprisingly to say the least1.

Despite my strong opinions about the validity of some of Whoop’s digital biomarkers, I don’t believe the company is malicious, nor do I think they intend to deceive consumers. What I do believe is that they, and other consumer health companies, are operating in a hyper-competitive environment where the reward for sensational and easily marketable features is increased consumer adoption and the penalty for conservative claims is irrelevance. In this environment the question isn’t whether any individual company will make unsubstantiated claims or market a feature their technology can’t support—instead, it’s who will be the first to do it, and how far they can stretch these limits until consumers loose faith in their technology.

To fully appreciate why the current generation of consumer health devices represents such a profound case of measurement mismatch, we need to start with what we know about human biology and health from a bottom-up perspective. Take anti-aging—the poster child for speculative consumer health claims. The past two decades of research, propelled by next generation sequencing, have shown aging to be a complex multi-system phenomenon involving cellular senescence, mitochondrial dysfunction, protein aggregation, genomic instability, and epigenetic drift. All of which are processes several layers of biological abstraction removed from anything a wrist-worn optical sensor can detect2.

The same principle applies to brain health and immune function among other areas of health. The most meaningful biomarkers exist at the levels of gene expression, protein abundance, metabolite concentrations, and methylation patterns. Measuring these things accurately requires high-throughput RNA sequencing, mass spectrometry, immunoassays, imaging techniques, and other technologies. A device that measures heart rate, skin conductance, and movement patterns is an entirely different universe of biological information.

This isn't to say that the physiological parameters measured by consumer devices are meaningless or lack utility. Heart rate variability does correlate with autonomic nervous system function, sleep architecture does relate to metabolic health, and activity patterns do influence cardiovascular risk. But correlation is not causation, and correlation is certainly not equivalent to direct measurement. When devices measure heart rate variability and claim to be assessing "recovery" or measure blood glucose and claim to measure "metabolic health" their providers are making conceptual leaps over gaps that cannot be spanned by objective fact.

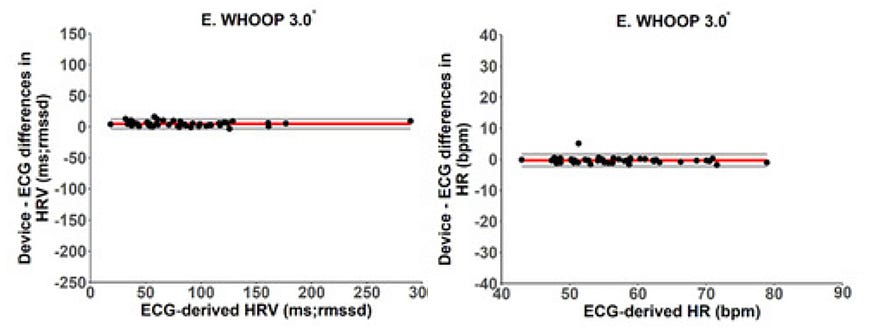

Whoop’s "Pace of Aging" score provides a perfect case study into how this measurement gap manifests itself in practice. Whoop, as company, has positioned its product as a leading form-first wearable3 and its devices genuinely excel at what their hardware is designed to measure — namely heart rate and heart rate variability.

The problems begin when accuracy with their primary sensing modality—photoplethysmography—becomes the basis for claims that venture far beyond what the underlying hardware and sensors can support. The biological age and pace of aging measurements are the most egregious examples, but they are hardly unique.

Consider what would actually be required to estimate biological age accurately. Morgan Levine and colleague’s DNAm PhenoAge, one of the more sophisticated approaches to biological age prediction, incorporates chronological age, albumin, creatinine, glucose, C-reactive protein, lymphocyte percentage, mean corpuscular volume, red cell distribution width, alkaline phosphatase, and white blood cell count in it’s model. Yet, even this approach has its limitations in that biological aging is organ-specific. Your liver, brain, and cardiovascular system don't age in lockstep, and as a result any single metric inevitably obscures important biological heterogeneity. Capturing this heterogeneity is possible, but it requires high-throughout proteomics, measuring thousands of plasma proteins simultaneously, as demonstrated in this seminal paper from of the Wyss-Coray lab at Stanford.

Whoop’s approach, by contrast, relies on algorithms trained on population-level data to identify correlations between lifestyle factors and age-related outcomes. In their own words, "Whoop Age and Pace of Aging are designed to reflect well-established links between behavior, physiology, and long-term health. While WHOOP Age correlates with perceived health and general wellness at a population level, there is no clinical benchmark for validating these metrics."4 This approach might have some predictive value at the population level, but presenting it as a precise measurement of biological age feels a bit suspect.

The tragedy is that Whoop’s underlying, unadulterated, measurements are valuable. They don’t even require inflated claims to justify their use. So, why then do they take this approach? The answer lies in what I call the single-point sensing trap. When you’ve built your entire brand around the premise that a wrist-worn band can provide comprehensive health insights— as Whoop claims with their promise to "improve performance, build healthier habits, and extend health span with continuous health monitoring"— you’ve painted yourself into a technological corner. To admit that holistic health monitoring might require multiple distributed sensing modalities would undermine what makes your product marketable in the first place.

This constraint creates a perverse innovation cycle. Instead of expand their sensing capabilities to match their ambitious claims, companies like Whoop are forced to stretch their existing sensor data even thinner, creating increasing elaborate algorithmic castles built on quicksand. Each new feature, from sleep coaching to strain optimization to biological age estimation, represents another layer of abstraction designed to extract insights that their hardware just can’t capture.

Meanwhile, a schism is starting to open in the consumer health space between companies doubling down on single-point sensing, like Whoop, and those that are beginning to embrace a distributed sensor architecture, which I’ve previously written about in Issue #48: Distributed by Design. Oura’s recent integration with Stelo speaks to this. When Oura acknowledges that ring-based measurements need to be complemented by continuous glucose data to provide meaningful metabolic insights, they're admitting something that should be obvious but remains unspoken: human biology is too complex for any single sensing modality to capture.

The transition from single-point to multi-point sensing enables something more profound that just measurement diversity; it opens the door to discovering network biomarkers, a conceptual framework that treats biological relationships rather than isolated metrics as the fundamental unit of health assessment.

Consider what this might mean for the biological age measurement that so captivated my friend. Instead of trying to compress the complexity of multi-system aging into a single score derived from heart rate and sleep patterns, imagine a distributed sensor network that treats aging as what it actually is: a heterogeneous, organ-specific, process with complex interdependencies. Such a system might integrate data from a smartwatch or ring, continuous glucose monitor, muscle oximeter, smartphone sensors (including the camera and microphone), and periodic laboratory biomarker panels. Rather than generating disparate data streams, these inputs would feed into models designed to map causal relationships and treat the network itself as the biomarker.

Additionally, by collecting continuous digital biomarkers alongside periodic molecular measurements, we can map the causal relationships between different layers of biological organization, creating a fundamentally different paradigm for personalized health monitoring than what exists today5. For example, we could build causal models that map how changes in your diet, exercise, and daily behaviors impact sleep quality, specific inflammatory markers, and digital biomarkers like HRV (and how these things in turn impact each other, mapping the various circular dependencies and chains of cause-and-effect).

The practical applications of this approach are many. Imagine you notice your heart rate variability declining over several weeks coincident with changes in sleep architecture, more volatile blood glucose measurements following meals, and mild muscle tension dysphonia sensed via your iPhone’s microphone. Traditional approaches might flag this as "low readiness", "high strain", or some other vague wellness claim. A network biomarkers approach, on the other hand, might recognize this pattern as a potential signal of infection or systemic inflammation and recommend targeted laboratory testing for specific inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-6, not only allowing for it’s predictions to be validated, but further feeding data into the causal models. Perhaps more importantly, by mapping causal chains between all of these variables, and the relative strength of those causal relationships, we can determine the most impactful interventions, which is something I’ve written about in Breaking Biometric Babel.

This also seems to align with Oura's thinking, as indicated by Maz Brumand, their VP of product, who told CNET: "By combining Stelo data with Oura's existing insights, we're empowering members to better understand the cause-and-effect relationships between eating patterns, energy, mood and recovery and ultimately make sustainable, science-backed lifestyle changes."

Seeing one of the biggest players in the industry embrace the aforementioned approach validates what should be clear: that the measurement gap that characterizes today's consumer health landscape isn't immutable. It's the predictable result of trying to extract complex biological insights from individual sensors measuring isolated parameters. However, as the industry shifts from single-point sensing to distributed sensing networks and network biomarkers, the door to genuine biological insights opens wide.

This transition will likely create a bifurcation in the market. Companies that continue building increasingly elaborate castles on quicksand—layering algorithmic complexity onto fundamentally inadequate sensing—will find their structures collapsing under their own weight as consumers become more sophisticated about what these devices can and cannot measure. Meanwhile, those embracing distributed sensing will capture the growing segment of users who want real, actionable, health insights.

The question isn't whether this shift will happen, but how quickly the industry will recognize that solid ground lies not in more clever algorithms, but in acknowledging the inherent complexity of human biology and building sensing architectures that match that complexity.

According to Whoop, "Whoop Age is a measure of your physiological age, which can be younger or older than your actual, chronological age." On Whoop’s support page they go on to explain how Whoop Age is calculated, stating "Whoop analyzes the following key metrics to determine your Whoop Age: Sleep, Strain, Fitness (Resting Heart Rate, VO2 Max, Lean Body Mass (if available).” In other words, Whoop claims to predict your age based on your sleep (loosely correlated with age), Strain (a made up measurement), resting heart rate (poor predictor of age within their target demographic), VO2 max (which their device can’t measure), and lean body mass (another metric they don’t measure)... seems legit.

Not to mention the fact that even the most precise aging clocks, utilizing proteomic data from blood or tissue biopsies, are only accurate at the organ-specific level. That is to say, the idea of a single "biological age" is unfounded in that different organs age at different rates, which could be uncouple from one another in the case of certain disease states.

I’ve written about the dichotomy between form-first and function-first wearable technology development in The Garden of Technological Possibilities.

Interestingly Whoop failed to mention the lack of clinical benchmarks or validation for their aging measurements in their marketing and the 42-page product release document titled "The Whoop Healthspan Feature: Advancing Personalized Longevity". Instead, it was briefly mentioned on their less publicly facing support page.

Doing so requires incorporating time-dependent relationships in multiomics data, implementing methods to deconvolute cause-and-effect relationships, and building systems that allow for easily mapping between different forms of biological data, from digital biomarkers to proteomic measurements, to outcomes, which i’ve written about here, here, and here respectively.

On the other hand, I think that sensor engineers are sometimes too pessimistic about what you can measure with a single sensor. For example, you wouldn't think that a PPG signal would allow you to do accurate sleep staging, or you wouldn't think that GPS sensor could detect depression, but both of those actually work quite well.

There's this weird thing about biological signals where everything is correlated with everything, so you can often infer the state of something indirectly with pretty high accuracy. Especially when what you're trying to predict is not something specific about an organ ("What is this person's leukocyte telomere length") but rather something about their whole body ("How many more years are they likely to live)

Brilliant analysis of the measurement gap problem. The single-point sensing trap you describe is spot-on, and I think it explains why so many health apps feel like they're overreaching. The network biomarkers framework makes way more sense than trying to compress multi-system aging into a single score from HRV data. I'm really curiou to see if the industry bifurcates like you suggest, or if regulation steps in first to reign in overstated claims.